"This Demo Could Have Been Better"

TL;DR

- Context is the silver bullet to nailing demos

- People’s attention sucks…so run with that

- Demos aren’t videos, they’re conversations

- People’s needs are more important than yours

- Be prepared with context about your audience

- A few key behaviors to improve presentations

Contents

- CONTEXT: Context Matters A Lot

- On Attention and Patience

- The Value of Real-time Interactive Demonstrations

- Your audience is the star of the show, not you

- Demo Preparation and Minimum-viable Context

- A few key behaviors to improve presentations

- Conclusion

CONTEXT: Context Matters A Lot

This is not clickbait, it’s my life

“This demo could have been better” was a polite piece of feedback I received on my first week of being a Sales Engineer for the first time back in 2013. Nick Olivo (a legend to those who’ve had the pleasure to work with him) said this because it was true. I had no idea what I was doing back then, he knew it, but still hired me. Part of the required reading during onboarding was “Great Demo!” even if by that time it was dated, because it was a solid basis for noob presenters like me to get under my belt.

I’ve been a software developer, a tech evangelist, a sales engineer, and a product manager. You know what all of these have in common? Each is in service to an audience.

Demos by Developers

A dev has to demo to the team, or better to stakeholders, or best to customers! No matter which of these audiences, making clear points and connecting them to the value the work provides to its users is critical for deepening domain context around their work and producing better, faster outcomes.

Demos by Evangelists/Advocates

Same with product evangelists (a.k.a. ‘advocates’) who live and breathe not only core capabilities, but fringe and brand-new ones of a product or service offering. They have very limited time between flights, conferences, user groups, customer on-sites, article writing, video producing, and partner meetings to learn this stuff and thus have to find ‘glory moments’ in demos.

Demos by Product Managers

Product managers are a bit different because usually they’ve already got a clear vision of how a feature should meet specific needs, and (hopefully) a few reference examples from customer champions involved in the early development of new features. Great product managers also use demo opportunities to learn in real-time, receiving and refactoring customer feedback about both the capability being demoed as well as the ways in which it is relayed (messaging, value props, format, cadence, reception).

Demos by …Sales Engineers…

Sales Engineers have huge amounts of ‘skin in the game’ about nailing demos, specifically, potential for commission. It’s not enough to show product capabilities…they must be relevant to specific needs of each prospective customer, rapidly get the business impact across, and demonstrably be better than competitive options that might address the same problem(s).

As someone who has personally borked (a technical term for screwing up) moments in demo meetings around new features but then quickly adjusted to fit, it’s an equally terrible feeling to not hit the mark as it is to how great it feels when you get great feedback for nailing a demo. Either way, it’s not as simple as “…because the presentation was/n’t there…”. Your ability to demo is one part of the coin and the other is a jumble of things about the audience.

The key point is…if people’s attention and cognitive limits are a known and largely unchangeable quantity…run with it. Don’t take it for granted or take advantage of it. Just understand the prevalence of these barriers to a great demo and front-load your own capabilities to handle them.

On Attention and Patience

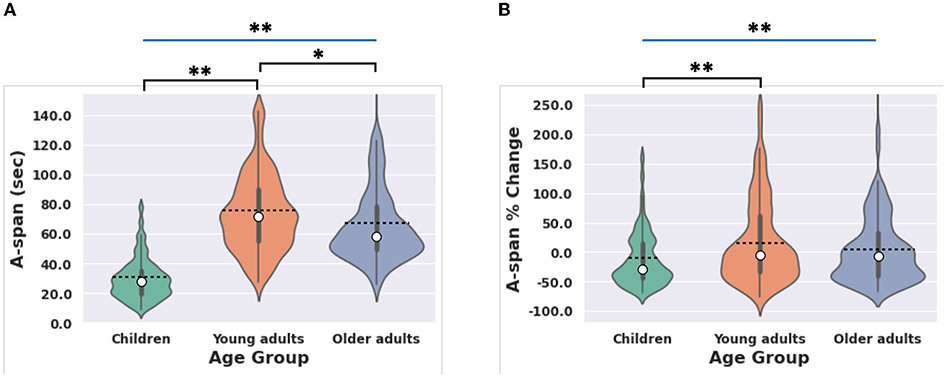

The average attention span of an adult is around one minute. Just look back at your last recorded presentation and count up the number of times you went WAY over that threshold on each slide.

(Source: National Library of Medicine, 2023 “Quantifying attention span across the lifespan”)

(Source: National Library of Medicine, 2023 “Quantifying attention span across the lifespan”)

I do it more than I’d like to admit, on zooms, over beer. My only consolation is that I’m getting more keenly aware of time spend as I get older. I also have teenagers in the house that have a lot to say, so I rack up ample practice being patient at home and not just at work.

Human attention is always divided

On your side of the remote conference call, you might think people are watching and listening to everything you do…but they’re not. They’re responding to co-workers, looking up details about your product (or you), doing email, or flipping tickets…until it sounds like something worth their attention happens. Don’t expect that their questions will be informed by things you’ve already said or shown. More than likely, you’re not that different, so anticipate this by dividing your presentation of features or larger compilations into very small sections.

BONUS HOMEWORK: what are the key segments/persona you demo to? Do you know what and how their attention is lost to other activities? How would you identify that this is happening, or how would you encourage it not to happen?

People have little patience, specifically for answers

Questions are not to be feared. In fact, they are one of the better ways for an audience to acknowledge their receipt of what you’re presenting. Answering questions succinctly and courteously is the silver bullet to keeping them from becoming objections-like injections.

When someone asks a question, acknowledging it, even if you can’t answer it to satisfaction in a timely manner right then and there is a trust-building technique. Repeating their name would be great…people love to hear their name (so long as it is properly pronounced)…and a thanks for it. Worst case, if it’s something you don’t know, you can always respectfully take it as a follow-up based on inputs from your team, diffusing the perception of aloofness.

Verbalize what is needed to answer the question at first, not more. A question such as “Do you support DevOps?” is vague and even possibly erroneous, but if your website and product boasts something as such, your immediate answer must be in the affirmative. ‘Yes’ or ‘well, yes’ is just fine, and if a question isn’t very specific and equally so the answer, it should be followed up with clarification.

If you didn’t hear something properly, apologize and ask for clarification (not reiteration). Consider a clarification a ‘dip in the bucket’ of their patience, but it is better to do so than provide an answer to some question they didn’t really ask. If you think they are really asking about something that’s not what they articulated (or well), you might use a “…what I think I heard was a question about…”

Questions and answers can elongate the time you have to present the main thing but there are polite ways to get around this potential issue. Preserving conversational flow is really important to leaving people with the accurate sense that you are genuine in your involvement and willing to help them. If Q&A is taking longer than desired, a polite way to get back on track is to say “this is a good topic, and in the interest of time, may we take it as a follow-up?” That way, the whole group’s time is respected and not dominated by one person’s agenda.

The Value of Real-time Interactive Demonstrations

The number one value of a real-time session to demonstrate software is human-to-human interactions, hopefully trust-earning and next steps accountability. It is not fact-finding, though the crappier documentation is, the more it becomes about otherwise trivialities like what might be Googled.

Think about it. Why would people, usually in different time zones, coordinate a live discussion together? If it’s not because of lacking information (or information gathering skills); it’s more often because people feel they can hold each other accountable for level understanding and eventually confidence in a decision. Leaving the watching of videos up to your team or co-workers when there’s a timeline on a decision makes it hard to ensure that everyone saw the same things and engaged their brains.

Videos are linear and can be paused whereas conversation is dynamic. One of the best things to do is ask before a session starts if it can be recorded, unless it is of a highly sensitive nature or permission is not granted. It’s better to ask and not get permission than have to say you don’t have a recording when a late-comer asks about it at the end of a meeting. When you do, turn the video around ASAP even if your follow-up communications are slower to complete.

What’s not in a video that IS in an interactive demo?

Videos are important because your team needs to sleep sometimes. Videos, however, age as your product changes. Demos on the other hand are different each time they occur which is great to ensure that the latest information is provided to an audience. Up-to-date and versioned documentation is important too. Each of these mediums come at different costs and should be applied based on the unique value they provide, not solely cost to the business.

What’s NOT in a video is the ability to ask very specific questions based on audience context, known before a demo or especially when not yet stated. Some answers also lead to other questions, deeper context, and more insight into more fundamental challenges a user may be facing.

A great representative of a solution maintains ‘audible readiness’ but also a portfolio of resource links for when questions that are easy to provide short affirmative answers on deserve more detail later. This keeps interactive time with an audience on track yet does not dismiss the importance of technical detail.

Another thing that you can’t get from a video is a chance to schedule follow-ups about specific outcomes of a demo session. Always know what the next steps are coming out of a demo and don’t expect others to be jotting these down. Certainly capture your own follow-up items but also notes about other moments in the conversation that may be relevant to sync with your team about afterward.

Opportunities are for LEARNING

Most importantly, the focus of every session demo or otherwise is to LEARN. The audience learns about your thing in a level manner and might learn technical details they couldn’t get from videos or docs. But ideally, YOU LEARN more about their deeper challenges, their imperatives, their timeframes, their decision process and criteria, and sometimes even key barriers (objections or concerns) they might have in the process of acquiring your thing.

A classic framework to discovering minimum-viable information about a prospect is “MEDDIC”, a slightly dated but still foundational sales process acronym coined by folks at PTC, which stands for:

- Metrics

- Economic buyer

- Decision criteria

- Decision process

- Identify pain

- Champion

As a technical resource in your sales team, you may not think all of these things are your responsibility to uncover and understand. Sometimes it’s early in a sales cycle with a prospect and they are forthcoming. Sometimes your sales rep already has a good sense of these (and hopefully has documented it somewhere you can already get to, such as your CRM).

However, the above points represent critical context that should ideally be known before hopping on and just doing a dog-and-pony-show demo. Ask your rep for these, not simply a blurb of context coming from an SDR short chat, get them used to your expectations that ‘we should be as informed as we can be to nail demos’, an intent which they benefit from as well.

Your audience is the star of the show, not you

You have needs. Money and attainment are paramount in sales, but so is training and staying up-to-date with your product capabilities or service offerings. We all want to feel like we’re doing our best too, and in the context of technical sessions like product demos, the optimal way to know if you are reaching that aim is for feedback.

It follows then that your audience (including your own team) is the star of the show, not you. Their needs are greater than yours if you want their money, plain and simple. In the book “Give to Get” Vishal Agarwal discusses how business leaders benefit from taking an in-service-to-others approach. Leaders aren’t just managers and executives, each person has a part to play in leadership. In sales, one of the best things you can do is to provide people what they value and you can uniquely deliver.

Sure, over-providing here often sets up unhealthy dependency, but giving a little before asking for something works better in the long-run with most relationships you build, even the short-term ones. We’re not talking tactical things like sending your reps follow-up answers, the slides from a session or forwarded zoom recordings.

Value to sales reps is progressing the sales cycle in an optimally positive direction and doing so in a timely manner.

Uncovering missing minimum-viable intel, exposing greater technical imperative and business impact, even working with an account champion to hone their internal pitches…these are very meaningful to increasing the confidence that a rep’s pipeline of key opportunities are as well-informed as possible, ultimately more likely to hit attainment goals.

Demo Preparation and Minimum-viable Context

There’s more than just one type of ‘demo’. An initial demo is very different from demoing advanced and new features. Demoing integrations can easily become a discussion about increasing the audience’s value to their own business through making room for new work by reducing toilsome manual steps or process faults. Each type of demo session requires different amounts of ‘minimum-viable context’.

Initial Demos with limited context

Just like a first date, you want to look and act your best. Demoing to an audience that you have no context about is more like a blind date. For initial demos, a few minimum-viables I benefit from are:

- Audience makeup in terms of roles and responsibilities

- A simple description of their current state

- What tools and platforms they’re currently using

- What brings them to looking for alternatives

- A few key things they said they really needed to see

With skilled conversation and time management, spending a few minutes up front confirming or completing your knowledge on the above ensures that your audience knows you are there for their benefit first and foremost. Much of the time, it should be mostly responses you already know or are likely to be the case. If not, you’ll all have it top-of-mind to highlight and address in the session.

If you have to do a demo with limited context up-front, you can take a few moments at the beginning to quickly mention what you plan to spend the time on. Also mention that your interruptible for live question that people think benefit the whole group, and other questions will certainly be followed up on later.

For worthwhile opportunities, initial demos should always lead to follow-up sessions on more specific areas. What you demo should be relevant to a prospect or customers needs. This gives you a certain amount of right-to-ask for more context rather than being a human livestream.

Canned Demos vs. Bite-sized Chunks

You should always be practiced on key elements of a ‘canned’ demo, but it should never be thought of as a one-shot session. Canned demos, while easy on the presenter’s cognitive load and especially so the more you have to do per week, lack personal connection between you and your audience or worse, your audience and the value of your thing. Sure, sometimes the customer thinks they just want a fly-over, but what they should get more is an opportunity to see and discuss the value of your thing in their context.

Each of the ‘elements’ in your canned demo should be short and highlight the value of some capability rather than simply how it works. A great way to talk about ‘value’ is to build up a set of audible-ready customer references to those who got the particular value from your thing. Some presenters like to stick to the “tell, show, tell” method where you say what you’re going to show, show it, and then summarize what was just shown. In my experience, each section should end with a simple pause for “…any questions or feedback on how this relates to your work?”

Being practiced at bite-sized chunks of demoable material also makes it easy for you to record them and use them elsewhere, such as sending them to customers in follow-up emails, marketing materials and documentation. But most importantly, bite-sizing your demo portfolio helps you remain nimble and able to properly pivot when a session takes an unexpected turn.

Advanced capabilities, new features, and integrations

Some things take longer than a few minutes to demo and in that case, be willing to skip less important things to remain on track and on time. Even with deep-dive topics, keep the demo surface area ‘bite-sized’ because the more succinct you can be with showing something on screen, the more time and opportunity there is to uncover context which can help to highlight the business (not simply technical) value of your thing.

You’ll get a lot of practice on the most valuable things to a product offering, but not with other more fringe capabilities. New features will not be as fully developed as later on and messaging on them will likely change. Integrations to external systems and tools bring additional risks into a demo. Mitigating that risk ultimately means having to be prepared to demo a lot of different things, even if you don’t pivot live in specific sessions. In an initial demo, if someone asks about integration to something, you can simply say ‘yes, we do’ and take an action item to schedule later context and deep-dive if they want to.

A great thing to do is to keep a list of topics and capabilities that come up, regularly re-prioritizing by frequency and comfortability, then use it as your own personal training/education curriculum. As you practice each topic, get it to the point where you can produce a short video, then store that and retain a public link to it for later use. This will come in handy not only for you to refresh yourself on messaging when an infrequently requested niche topic comes around again, but also for other technical team mates as well.

Environments are always tricky. Even if your ‘environment’ is all in a SaaS offering or cloud resource, repeatability of level configuration for the demo is important. No one is going to keep your demos clean and fault-free but you. If you do use shared resources or environments with other team members, make sure there are clear boundaries and risk management measures in place. Isolate resources when possible, and when not just make sure others who share those resources are in regular sync (such as sales engineers team meetings) about norms and changes to them.

A few key behaviors to improve presentations

Every technical presenter brings their own unique set of skills, knowledge, finesse, and personality traits to sessions. But again, the presenter isn’t the star of the show, it’s the audience. In all my years, I keep coming back to a few key behaviors I always see as areas for improvement:

1. Verbalization and Visuals

Whatever language you speak, it should be understandable by your audience. Practice speaking in a calm, casual, and measured cadence. Excitement can be heard in what is said, but often leads to loud talking. Direct your answers and questions to specific individuals. Be okay with a little ‘dead air’ after asking a question because often people need a little time to think. Ask yourself three things about what you’re verbalizing:

- Does this need to be said?

- Does this need to be said right now?

- Does this need to be said by me?

Likewise, visuals are important, even to non-visual thinkers. A picture is worth a thousand words or somesuch, so the right or wrong visual amplifies the correctness between intent and what is relayed. The less complex, the better, usually. If there are words on a screen that don’t match up with what’s being said, it’s simply adding cognitive load to listeners. If there are too many shapes, if the text is too small to read, or too many colors or patterns, it detracts from the intent of the message or communication.

2. Listening and Observations

Listening in sales is about hearing, processing, and developing information into an accurate situational model. Some information can be treated as fact, such as “what git repo platform do you use”, but other information needs to be vetted before running with. Some audience members will state something as fact and no one wants to correct them in a group setting, thus audience size (large, small, one-on-one) presents different listening opportunities.

Humans are susceptible to and carry many biases. It is important to avoid ‘happy ears’, hearing only what you think is optimal to your aim, by reflecting on conversation notes and discussing sessions with other team members. Each person has their own ‘observations’ and at the end of the day, the more informed and accurate intel is about a sales cycle, the more likely the team gets what they want from it.

3. Genuinity and Trust-building

In my honest opinion, I truly believe that most people respond well to genuinity in others. Of course, interactions have to be underwritten by professionalism, usefulness, and timeliness; but every seasoned buyer knows what the disingenuine sales pitch looks like and it’s a turn-off every time. There’s not a recipe for genuinity, though the closest I can think of is:

- if you say you’ll do something, do it

- listen when someone else speaks; if they speak less than they listen, ask them questions

- don’t pretend to know things you don’t; show a little passion for the things you know well

- show your belief that what you are doing is worth their time

- be considerate of others, make room for more than just two people

The difficulty with building trust is that it takes time…and consistency. We have very little time and so many interactions all day, that the best you can do is to be consistent in each one. Look for feedback that can help you improve, occasionally solicit that from others, and never talk behind people’s back. Given time, the relationships worth building will become apparent.

Conclusion

Being able to demonstrate technical topics and products isn’t simply about showing features. Humans are not YouTube or documentation, so don’t act like those things. Seeking and putting to use context in demonstrations turns sessions into a treasure trove of better intel, but it takes practice and willingness to improve to really hone these skills. Adapt to peoples’ appetite and attention because giving them what they need earns you permission to ask for what you need from them. The more context you have, the more impactful your interactions with audiences will be.