Defining ‘Developer’

It may sound like an unnecessary errand in 2021 to have to define what “developer” (“programmer”) means, but once again I find myself in the complimentary and contradictory position of having to disambiguate what people in software mean when they casually say “dev” or “developer” in rooms of like-minded individuals.

TL;DR

A ‘developer’ is someone who contributes functionality, typically in the form of code, to a product or service that runs in production to drive the material goal of an organization. This usually means:

- Translating user stories into running software

- Further detailing requirements of above stories

- Estimating and/or preparing to implement changes

- Primarily adding new, then secondarily updating or fixing existing, functionality

- Writing unit tests which verify core code components of the above changes

- Consulting with other stakeholders (architects, users, operations engineers)

- Describing the material operating conditions of the functionality

It does not primarily mean, though sometimes involves:

- writing pipeline or infra-as code

- whiling hours away trying to get Kubernetes to do what you want it to do

- writing functional and

non-functionaloperational tests - clicking around through cloud consoles like AWS/Azure/GCP to get software to work

In short, the ‘magic’ is consuming whatever it takes to produce software. I dare ‘test-ers’, ‘DevOps’, or product managers/owners to do this. I fucking dare them, and if they do, it will still be something a professional programmer has to rewrite so that it A) makes sense to anyone else, B) is maintainable once shipped, and C) makes everyone money.

A Developer’s Best (Local) Goal

The best goal of a developer is to safely and efficiently translate user needs into working software that achieves their organization’s goal, preferably better than other attempts to do the same in other industryAnd examples. This is a “local optima” or local goal and contributes to their team’s less local one, which is the same as above, but with additional liberties and constraints that change the dynamics of how best to accomplish the goal.

A Developer’s Dis/Optimal Approach

Regarding the latter, though every individual in the team is subject to personal ambitions and inhibitions, it is shitty politics to live by them. In the past, I’ve experienced colleagues who do this, and not only do they contribute to pathological outcomes, they undermine their own effectiveness and sense of satisfaction from their work.

Most developers, well, we work in teams. Even if we are “ICs” (individual contributors), we are surrounded by others that need what we produce and need us to be at our best, not just from an individual perspective, but for others around us. If you doubt this perspective, consider trying to get anything done without having working relationships with other team members that help you do the above and below bulleted activities.

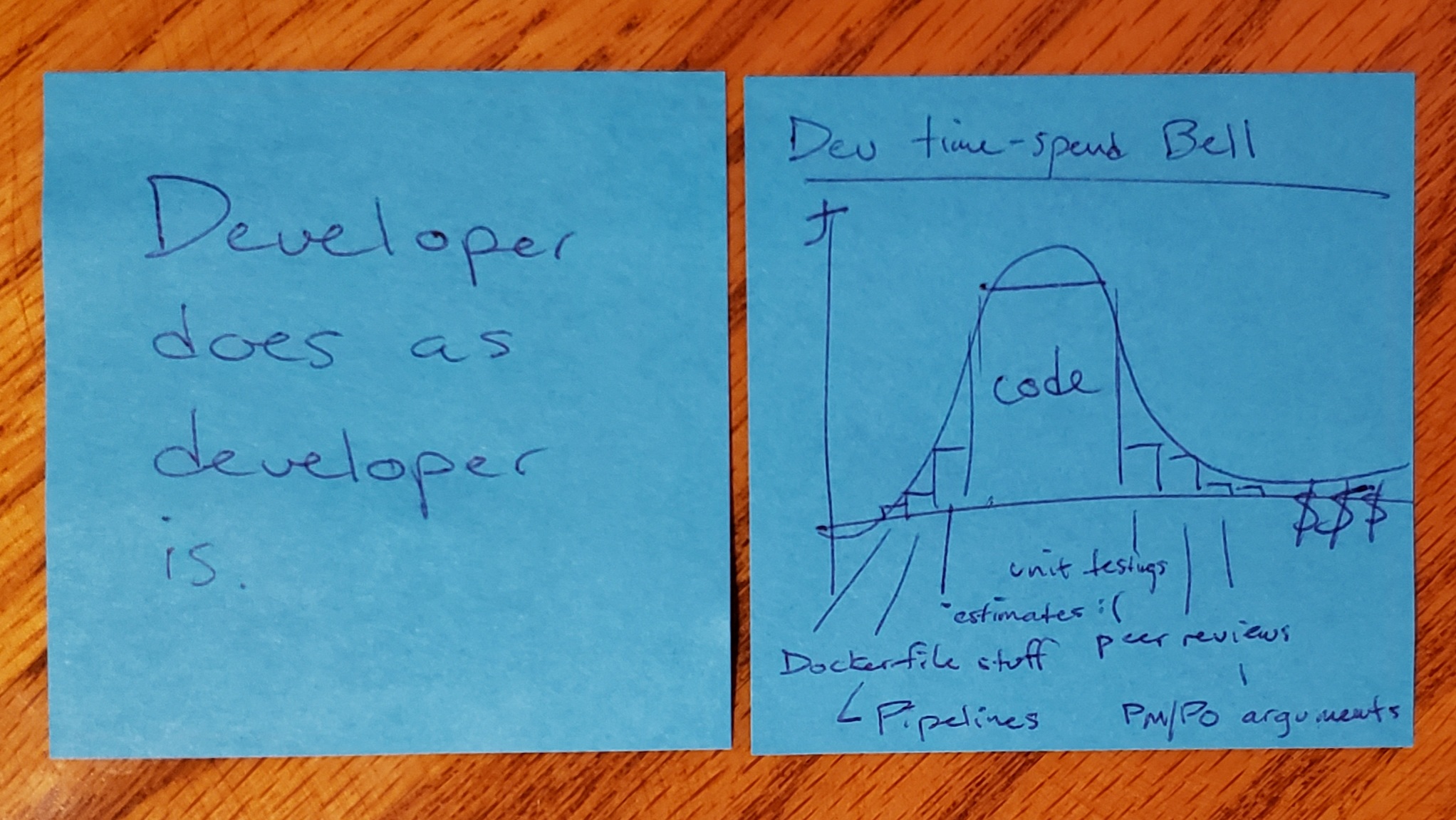

So, from a tactical perspective, yes, the above bullet points about what a developer does represents the 80% under the Bell curve of what IMO a developer does. As a life-long programmer (skill and curiosity-driven, not vocational ‘developer’), and if you are in fact a developer, you may find yourself doing many other things like:

- screwing around with an issue tracking systems

- contributing your thoughts to peer reviews

- playing video or board games with some colleagues

- learning about new technologies, usually on your own time/dime

- defending your position against product managers/owners who skip O-ring warnings

This doesn’t change the fact that if your primary goal is aligned with the above TL;DR, you are what I consider a ‘developer’. You are not a ‘tester’ (though sometimes you write tests) or a ‘product manager’ (though sometimes you have to fill knowledge gaps) or an accountant or a physicist or porpoises or even a manager (though you may have direct reports or lead a team of engineers)…the direct output of your work is ‘working software that achieves the organization’s goal’.

The Organization’s (Global) Goal

For most organizations, even non-profit ones, what looks like a developer doing their job well is to produce software that makes or receives money, or in some indirect but immediate way contribute to that end. Code can be many things, compilable or interpreted, imperative or declarative (or functional, etc.), sometimes even supportive of others doing those things (such as in the case of infrastructure-as-code for the release process). But never forget that:

The Goal of every organization is to make money, therefore so is yours

For any given profitable startup in “zoos next to the dragon sanctuary and unicorn exhibit”, or even run-of-the-mill enterprise Fortune 100 that can retain long-term talent (equally rare), revenue-as-code isn’t hard to argue about. But for NPOs, let me walk you through it.

Two sentient beings that are moving towards a common goal need to work together. To register as a non-profit, at least in most countries that allow for it, you need a ‘board’…a group of individuals that can agree on a charter…and a charter, which includes goals. Non-profits either burn out on an all-volunteer model or hire/retain qualified [enough] individuals to drive and achieve the charter mission, or iterate on what should-be/is achievable at any given phase of the NPO. If an NPO is truly worth existing for any matter of time, money comes into play, either in management thereof or in order to compensate for said expertise and efforts. To generate revenue in any venture related to the software industry, at some point, software engineers are required. Even if they are volunteer, the non-profit organization needs to generate streams of revenue, for philanthropic targets, and sometimes to support the organization’s core function to do so. NPOs need to ‘make money’ to survive, either to funnel to and justify their altruisms or/and to do that via skilled and focused professionals.

Developer-adjacent Likenesses

If you’re still not convinced that I’ve laid out a Goal, Approach, Outcomes and Tactics that sufficiently clarify what a ‘developer’ is uniquely, let me try a visual I’ve been working on called “A Dev Does as a Dev Is”:

In essence, think honestly about where you most feel comfortable. If that’s not writing code with a clear mission and autonomy to implement well-understood requirements in some type of code, then you’re not a programmer (disambiguation of ‘developer’). If you are more on the problem-solving side, which is perfectly fair, you’re still a dev, and code is a material part of your day-to-day.

If you spend most of your time trying to avoid situations where you have to “resort to code”, then you’re not what I’d called a ‘developer’. Not that a ‘good developer’ will rush to code any chance they get (this would also be an anti-pattern), but that the outputs of a ‘developer’ are primarily measured by working software that achieves their organization’s goal’.

NOTE: if you are a non-hashtag ‘DevOps’ person, you may be a half dev (like SRE time-spend) and half everything else that your organization needs. In this you are a special snowflake and worth every penny your company is (or should be) well-paying for you, since you think holistically about two sides of your work and of others’ work.

This is my blog and I can say whatever I want. If you don’t like it, feel free to hit me up on Twitter or LinkedIn, quote and hate me, or better, leave useful comments that further this dialog.