Performance Is (Still) a Feature, Not a Test!

Since I presented the following perspective at APIStrat Chicago 2014, I've had many opportunities to clarify and deepen it within the context of Agile and DevOps development:

It's more productive to view system performance as a feature than to view it as a set of tests you run occasionally.

The more teams I work with, the more I see how performance as a critical aspect of their products. But why is performance so important?

'Fast' Is a Subconscious User Expectation

Whether you're building an API, an app, or whatever, its consumers (people, processes) don't want to wait around. If your software is slow, it becomes a bottleneck to whatever real-world process it facilitates.

Your Facebook feed is a perfect example. If it is even marginally slower to scroll through it today than it was yesterday, if it is glitchy, halty, or jenky in any way, your experience turns from dopamine-inducing self-gratification to epinephrine fueled thoughts of tossing your phone into the nearest body of water. Facebook engineers know this, which is why they build data centers to test and monitor mobile performance on a per-commit basis. For them, this isn't a luxury; it's a hard requirement, as it is for all of us whether we choose to address it or not. Performance is everyone's problem.

Performance is as critical to delighting people as delivering them features they like. This is why session abandonment rates are a key metric on Cyber Monday.

'Slow' Compounds Quickly

Performance is a measurement of availability over time, and time always marches forward. Performance is an aggregate of many dependent systems, and even just one slow link can cause an otherwise blazingly fast process to grind to a halt long enough for people to turn around and walk the other way.

Consider a mobile app; performance is everything. The development team slaves over which list component scrolls faster and more smoothly, spends hours getting asynchronous calls and spinners to provide the user critical feedback so that they don't think the app has crashed. Then a single misbehaving REST call to some external web API suddenly slows by 50% and the whole user experience is untenable.

The performance of a system is only as strong as it's weakest link. In technical terms, this is about risk. You at least need to know the risk introduced by each component of a system; only then can you chose how to mitigate the risk accordingly. 'Risk' is a huge theme in ISO 29119 and the upcoming IEEE 2675 draft I'm working on, and any seasoned architect would know why it matters.

Fitting Performance into Feature Work

Working on 'performance' and working on a feature shouldn't be two separate things. Automotive designers don't do this when they build car engines and performance is paramount throughout even the assembly process as well. Neither should it be separate in software development.

However, in practice if you've never run a load test, tracked power consumption of a subroutine or analyzed aggregate results, it will be different than building stuff for sure. Comfortability and efficiency come with experience. A lack of experience or familiarity doesn't remove the need for something critical to occur; it accelerates the need to ask how to get it done.

A reliable code pipeline and testing schedule make all the difference here. Many performance issues take time or dramatic conditions to expose, such as battery degradation, load balancing, and memory leaks. In these cases, it isn't feasible to execute long-running performance tests for every code check-in.

What does this mean for code contributors? Since they are still responsible for meeting performance criteria, it means that they can't always press the 'done' button today. It means we need reliable delivery pipelines to push code through that checks its performance pragmatically. As pressure to deliver value incrementally mounts, developers are taking responsibility for the build and deployment process through technologies like Docker, Jenkins Pipeline, and Puppet.

It also means that we need to adopt a testing schedule that meets the desired development cadence and real-world constrains on time or infrastructure:

- Run small performance checks on all new work (new screens, endpoints, etc.)

- Run local baselines and compare before individual contributors check in code

- Schedule long-running (anything slower than 2mins) performance tests into pipeline stage after build verification in parallel

- Schedule nightly performance regression checks on all critical risk workflows (i.e. login, checkout, submit claim, etc.)

How Do You Bake Performance Into Development?

While it's perfectly fine to adopt patterns like 'spike and stabilize' on feature development, stabilization is a required payback of the technical debt you incur when your development spikes. To 'stabilize' isn't just to make the code work, it's to make it work well. This includes performance (not just acceptance) criteria to be considered complete.

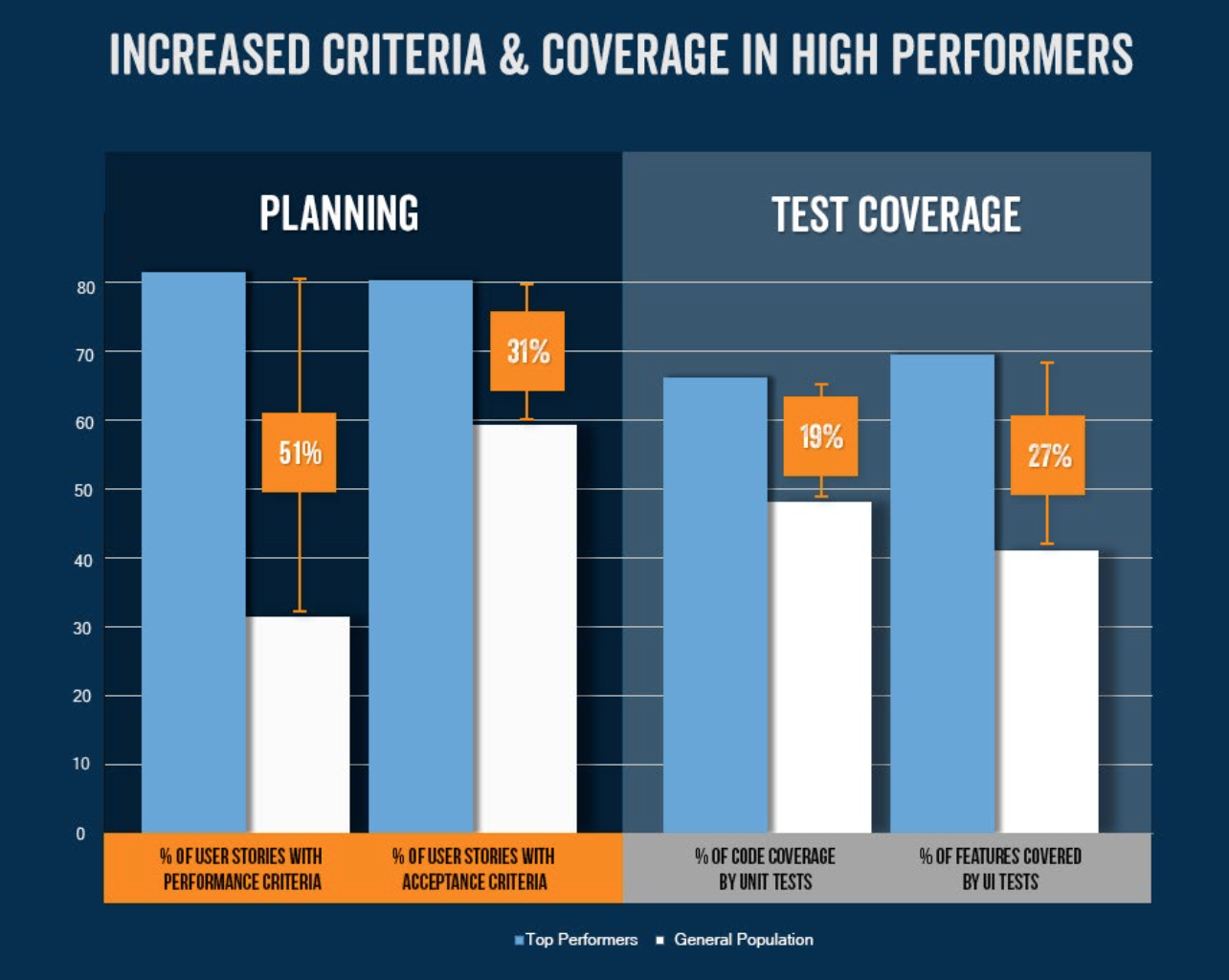

A great place to start making measurable performance improvements is to measure performance objectively. Every user story should contain solid performance criteria, just as it should with acceptance criteria. In recent joint research, I found that higher performing development teams include performance criteria on 50% more of their user stories.

In other words, embedding tangible performance expectations in your user stories bakes performance in to the resulting system.

There are a lot of sub-topics under the umbrella term "performance". When we get down to brass tacks, measuring performance characteristics often boils down to three aspects: throughput, reliability, and scalability. I'm a huge fan of load testing because it helps to verify all three measurable aspects of performance.

Throughput: from a good load test, you can objectively track throughput metrics like transactions/sec, time-to-first-byte (and last byte), and distribution of resource usage (i.e. are all CPUs being used efficiently). These give you a raw and necessarily granular level of detail that can be monitored and visualized in stand-ups and deep-dives equally.

Reliability: load tests also exercise your code far more than you can independently. It takes exercise to expose if a process is unreliable; concurrency in a load test is like exercise on steroids. Load tests can act as your robot army, especially when infrastructure or configuration changes push you into unknown risk territory.

Scalability: often, scalability mechanisms like load balancing, dynamic provisioning, and network shaping throw unexpected curveballs into your user's experience. Unless you are practicing a near-religious level of control over deployment of code, infrastructure, and configuration changes into production, you run the risk of affecting real users (i.e. your paycheck). Load tests are a great way to see what happens ahead of time.

Short, Iterative Load Testing Fits Development Cycles

I am currently working with a client to load test their APIs, to simulate mobile client bursts of traffic that represent real-world scenarios. After a few rounds of testing, we've resolve many obvious issues, such as:

- Overly verbose logs that write to SQL and/or disk

- Parameter formats that cause server-side parsing errors

- Throughput restrictions against other 3rd-party APIs (Google, Apple)

- Static data that doesn't exercise the system sufficiently

- Large images stored as SQL blobs with no caching

We've been able to work through most of these issues quickly in test/fail/fix/re-test cycles, where we conduct short all-hands sessions with a developer, test engineer, and myself. After a quick review of significant changes since the last session (i.e. code, test, infrastructure, configuration), we use BlazeMeter to kick of a new API load test written in jMeter and monitor the server in real-time. We've been able to rapidly resolve a few anticipated, backlogged issues as well as learn about new problems that are likely to arise at future usage tiers.

The key here is to 'anticipate iterative re-testing'. Again I say: "performance is a feature, not a test". It WILL require re-design and re-shaping as the code changes and system behaviors are better understood. It's not a one-time thing to verify how a dynamic system behaves given a particular usage pattern.

The outcome from a business perspective of this load testing is that this new system is perceived to be far less of a risky venture, and more the innovation investment needed to improve sales and the future of their digital strategy.

Performance really does matter to everyone. That's why I'm available to chat with you about it any time. Ping me on Twitter and we'll take it from there.